Mewing has emerged from a niche orthodontic concept to a global viral trend, promising a naturally enhanced jawline and improved overall health.

This comprehensive guide will delve into the technique, the controversial science behind it, and the practical steps you can take to understand this practice.

We will explore the principles established by the Mew family and dissect the common mistakes that can hinder progress.

Understanding the proper application of tongue posture is the first step toward unlocking its potential benefits.

1: Beginner’s Guide to Mewing

Mewing is fundamentally the practice of maintaining correct tongue posture.

The goal is to rest the entire tongue against the roof of the mouth.

This includes the tip, the middle, and crucially, the back third of the tongue.

The correct position is achieved by lightly suctioning the tongue upwards.

Imagine saying the word “sing” and holding the position of your tongue at the end of the word.

This action engages the muscles that lift the tongue and palate.

The pressure should be gentle but firm enough to create a seal.

It is essential that the front teeth do not touch the tongue.

The lips should be sealed, and breathing must occur exclusively through the nose.

Mewing is not a forceful exercise but a habitual resting posture.

Consistency is far more important than intensity in this practice.

Beginners should focus on awareness and gradually increase the duration of correct posture.

The initial feeling may be one of strain or fatigue in the muscles under the chin.

This sensation is often referred to as the “mewing burn” and indicates muscle engagement.

Over time, this posture should become the default, subconscious state.

The practice of mewing is a continuous, low-force application of pressure.

It is designed to stimulate the maxilla, or upper jaw, which is the foundation of the mid-face.

The tongue acts as a natural orthopedic appliance.

It provides the necessary upward and forward force to counteract the downward pull of gravity and poor posture.

For many, the initial challenge is simply maintaining the back third of the tongue in the correct position.

This area is often weak due to years of mouth breathing and improper swallowing.

A common technique to help engage the back is the “swallow-hold” method.

Swallow normally and then freeze the tongue in the position it naturally lands.

This frozen position is often the correct full-palate suction hold.

The sensation of the soft palate being lifted is a key indicator of success.

The tongue should feel like it is creating a vacuum against the roof of the mouth.

This vacuum is what provides the constant, gentle pressure.

Over time, the muscles will strengthen, and the posture will become effortless.

It is crucial to remember that mewing is a marathon, not a sprint.

Results are measured in months and years, not days or weeks.

The commitment to this 24/7 tongue posture is the single most important factor.

It is a fundamental shift in a deeply ingrained habit.

This shift requires constant mindfulness, especially during sleep.

Many practitioners use mouth tape to ensure nasal breathing throughout the night.

The combination of daytime awareness and nighttime reinforcement accelerates the process.

The aesthetic benefits are a secondary, though welcome, outcome of improved function.

The primary benefit is the establishment of a proper oral resting posture.

This posture is what nature intended for optimal human development.

2: Dr. Mike Mew & Orthotropics

The practice of mewing is named after Dr. John Mew and his son, Dr. Mike Mew.

They are British orthodontists who pioneered the concept of Orthotropics.

Orthotropics is a specialized form of orthodontics focused on guiding facial growth.

The core belief is that facial structure is primarily determined by environmental factors, not genetics.

These environmental factors include posture, diet, and most importantly, oral posture.

Dr. Mike Mew popularized the term “mewing” through his online presence and educational videos.

He argues that modern soft diets and poor oral habits have led to recessed jaws and crowded teeth.

Orthotropics aims to correct these issues by promoting natural, forward facial growth.

This is typically achieved through proper tongue posture and the use of specialized appliances in children.

The goal is to create a wider palate and a more prominent jawline.

It is important to note that Orthotropics remains a highly controversial field within mainstream dentistry.

Many established orthodontic bodies do not recognize it as a scientifically proven treatment.

Dr. Mike Mew has faced professional scrutiny for his unconventional methods and public advocacy.

Despite the controversy, his work has inspired millions to reconsider their oral habits.

Elaborating on Orthotropics and the Scientific Divide

Dr. John Mew first developed the principles of Orthotropics in the 1960s.

His work was a direct challenge to the prevailing orthodontic practice of tooth extraction.

He argued that extracting teeth to make room for a crowded mouth was a flawed approach.

Extraction, he believed, often led to a retruded, or backward-growing, jaw.

Orthotropics, meaning “correct growth,” seeks to expand the jaw naturally.

The philosophy is rooted in the idea of epigenetics.

Epigenetics suggests that genes are expressed differently based on environmental input.

In this context, oral posture and diet are the environmental inputs.

Dr. Mike Mew has continued his father’s work, bringing it to a global audience.

He often uses the analogy of a tree growing in a strong wind.

The wind, representing environmental forces, shapes the tree’s growth.

Similarly, the constant pressure of the tongue and the act of chewing shape the face.

The Orthotropic treatment for children often involves removable appliances.

These appliances are designed to widen the palate and encourage forward growth.

The appliances work in conjunction with the child’s natural growth processes.

The treatment is typically initiated at a young age, ideally between five and nine.

This early intervention aims to prevent the need for more invasive procedures later.

The controversy stems from the lack of large-scale, randomized controlled trials.

The scientific community requires rigorous data to validate a new medical treatment.

Critics argue that the observed changes are within the range of normal growth variation.

They also point to the potential for relapse after the treatment is complete.

Despite the criticism, the Orthotropics movement has fostered a community of dedicated practitioners.

These practitioners believe they are addressing the root cause of malocclusion and facial disharmony.

The debate highlights a fundamental difference in approach to orthodontics.

One side focuses on tooth alignment, while the other focuses on facial harmony and airway function.

The public interest in mewing suggests a growing dissatisfaction with traditional methods.

3: Does Mewing Work?

The question of whether mewing “works” depends heavily on the definition of success.

From a scientific standpoint, credible evidence is currently lacking to support claims of skeletal change in adults.

Mainstream orthodontics maintains that significant bone remodeling is not possible through tongue pressure alone after growth plates have fused.

However, proponents often cite anecdotal evidence and before-and-after photos as proof of efficacy.

The perceived improvements are often attributed to changes in muscle tone and posture.

When the tongue is correctly positioned, it can tighten the submental area, reducing the appearance of a double chin.

This muscular change can create the illusion of a sharper, more defined jawline.

Furthermore, the consistent practice of mewing reinforces good head and neck posture.

Improved head posture alone can dramatically enhance facial aesthetics.

In children and adolescents, whose facial bones are still developing, the principles of Orthotropics may have a more pronounced effect.

The consistent upward pressure is theorized to encourage forward growth of the maxilla.

This forward growth is believed to prevent the downward and backward growth associated with poor oral habits.

Ultimately, while the aesthetic results are often subjective and muscular, the practice promotes undeniably healthy habits like nasal breathing.

The Nuance of Efficacy: Skeletal vs. Muscular Change

To fully address the question of efficacy, we must distinguish between two types of change.

The first is skeletal change, which involves the actual remodeling of bone tissue.

The second is muscular and soft tissue change, which affects appearance but not the underlying bone.

In adults, the most reliable and immediate results are muscular.

The toning of the suprahyoid muscles is a physiological certainty.

This toning effect is responsible for the visible reduction in submental fat and skin laxity.

The improved definition is a result of the tongue acting as an internal support structure.

It is similar to how core exercises can flatten the stomach without changing the rib cage.

The aesthetic benefit is real, even if the bone remains unchanged.

The improvement in head posture is another powerful non-skeletal factor.

Forward head posture is endemic in the digital age.

It causes the neck to jut forward, making the jawline appear weak and recessed.

Mewing encourages the head to retract over the spine.

This simple postural correction instantly makes the jawline look sharper.

It also reduces strain on the neck and upper back muscles.

For children, the potential for skeletal change is the central argument.

The maxilla is composed of multiple bones that fuse over time.

Applying gentle, constant pressure during the growth phase is theorized to influence this fusion.

This influence is the basis for the use of palatal expanders in traditional orthodontics.

Mewing is essentially a natural, internal palatal expander.

The debate is not about whether bone can be moved, but whether the tongue alone can exert enough force.

The consensus is that while the tongue is a powerful muscle, its effect is limited after puberty.

Therefore, adults should focus on the postural and muscular benefits.

These benefits are significant for both appearance and health.

The pursuit of mewing should be viewed as a commitment to optimal physiological function.

4: Sharper Jawline Anatomy

The appearance of a sharp jawline is a complex interplay of bone structure, muscle, and fat distribution.

Mewing primarily targets the suprahyoid muscles and the masseter muscles.

The suprahyoid muscles are a group of muscles located above the hyoid bone, beneath the chin.

When the back of the tongue is engaged, these muscles are activated and toned.

This toning effect is what lifts the soft tissue under the chin, creating a more taut appearance.

The masseter muscles, located at the angle of the jaw, are responsible for chewing.

While mewing itself does not directly work the masseters, it is often paired with hard chewing exercises.

Increased masseter activity can lead to hypertrophy, or growth, of these muscles.

Larger masseter muscles contribute to a wider, more square jaw angle.

The underlying bone structure, the mandible (lower jaw) and the maxilla (upper jaw), provides the framework.

Mewing advocates suggest that the upward force on the maxilla can cause it to move forward and upward.

This movement, known as maxillary protraction, is the key to a more attractive facial profile.

A well-developed maxilla provides better support for the nose and cheekbones.

The overall effect of correct tongue posture is a subtle but powerful repositioning of the soft tissues of the face and neck.

Deep Dive into Jawline Muscle Engagement

A detailed understanding of the muscles involved is key to effective mewing.

The Mylohyoid muscle is perhaps the most critical player.

It forms the muscular floor of the mouth.

When the entire tongue is suctioned up, the mylohyoid is activated and strengthened.

This action pulls the soft tissues upward and backward, tightening the area beneath the chin.

The Geniohyoid muscle also plays a role in pulling the hyoid bone forward and upward.

These muscles work in concert to maintain the elevated tongue position.

The masseter muscles, while not directly involved in tongue posture, are crucial for jaw development.

They are the primary muscles of mastication, or chewing.

The masseters are powerful and can grow significantly with increased use.

This growth is what creates the coveted square jaw angle.

The temporalis muscle, another chewing muscle, is located on the side of the head.

It is also strengthened by hard chewing, contributing to overall facial muscle tone.

The bone structure itself is influenced by the forces exerted upon it.

This is known as Wolff’s Law, which states that bone adapts to the loads under which it is placed.

The constant, gentle pressure of the tongue is the load in the case of the maxilla.

The powerful force of chewing is the load in the case of the mandible.

The synergy between these two forces is what Orthotropics aims to harness.

The goal is to create a harmonious balance between the muscles and the bone structure.

A strong, well-developed jawline is a sign of a healthy, functional oral system.

It is a byproduct of a lifetime of correct oral habits.

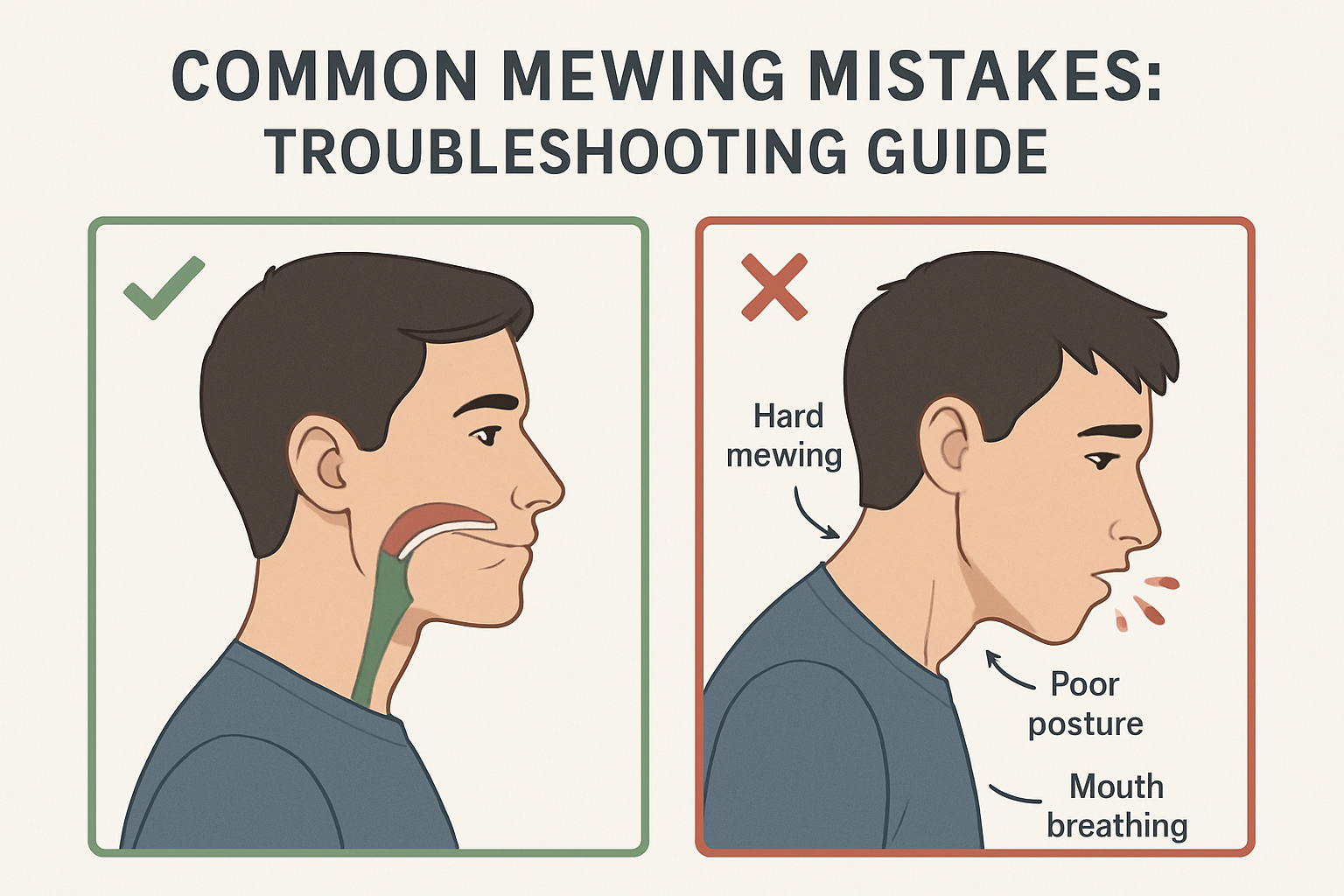

5: Common Mistakes

Incorrect mewing technique can be ineffective at best and potentially harmful at worst.

One of the most common errors is only engaging the tip of the tongue.

The back third of the tongue is the most crucial part for applying pressure to the maxilla.

Failing to engage the back third means the pressure is insufficient to create any structural change.

Another frequent mistake is touching the front teeth with the tip of the tongue.

This can inadvertently push the teeth forward, leading to dental misalignment or flaring.

The tongue should rest just behind the front teeth, on the incisive papilla.

Forcing the tongue with excessive, painful pressure is also counterproductive.

Mewing should be a light, constant pressure, not a strenuous workout.

Over-forcing can lead to jaw pain, headaches, or temporomandibular joint (TMJ) issues.

Mouth breathing while attempting to mew is a fundamental contradiction.

The lips must be sealed, and the airway must be clear for nasal breathing.

Mouth breathing negates the entire purpose of the practice, which is to encourage proper airway function.

Finally, inconsistency is the single greatest barrier to seeing results.

Mewing is a 24/7 commitment, not a few minutes of exercise per day.

Correcting these mistakes involves a constant focus on full tongue suction and nasal breathing.

Avoiding and Correcting Common Mewing Errors

The journey to correct mewing is often fraught with subtle, yet significant, errors.

The mistake of tip-only mewing is the most pervasive.

To correct this, focus on the posterior third of the tongue.

Try making a clicking sound with your tongue.

The part of the tongue that remains suctioned to the palate after the click is the area you need to engage.

The front teeth touching error can be corrected by placing the tongue slightly further back.

The correct spot is the rugae, the ridges just behind the front teeth.

The tip should rest lightly, not press forcefully.

If you experience jaw pain or TMJ discomfort, you are likely forcing the tongue.

Immediately reduce the intensity of the pressure.

Mewing should be a relaxed, sustainable posture, not a strain.

If pain persists, consult a dentist or a myofunctional therapist.

The issue of inconsistent practice requires a behavioral solution.

Use visual cues, such as sticky notes on mirrors or computer screens, to remind yourself.

Set hourly alarms on your phone to check your tongue posture.

Make mewing a conscious habit before it can become an unconscious one.

The most dangerous mistake is obstructing the airway.

If mewing makes it difficult to breathe through your nose, stop immediately.

This may indicate a pre-existing issue, such as a deviated septum or a narrow palate.

Consult an Ear, Nose, and Throat (ENT) specialist for an evaluation.

Mewing should always improve breathing, never hinder it.

The correct technique involves a gentle, upward force that opens the airway.

Correcting these errors is a process of re-education and patience.

It is about retraining muscles that have been dormant for years.

6: Breathing & Health

The health benefits associated with mewing are often more tangible and scientifically supported than the aesthetic claims.

Mewing inherently promotes nasal breathing over mouth breathing.

Nasal breathing is the natural and healthier way for humans to respire.

The nose filters, warms, and humidifies the air before it reaches the lungs.

This process improves oxygen absorption and overall respiratory health.

Mouth breathing, conversely, is linked to a host of negative health outcomes.

These include dry mouth, increased risk of dental decay, and poor sleep quality.

The constant pressure of the tongue on the palate is theorized to widen the upper airway.

A wider airway can be instrumental in reducing or eliminating snoring.

It may also help mitigate symptoms of sleep apnea, a serious sleep disorder.

By keeping the tongue off the floor of the mouth, it is less likely to collapse into the throat during sleep.

Furthermore, nasal breathing stimulates the production of nitric oxide.

Nitric oxide is a vasodilator that improves blood flow and oxygen delivery throughout the body.

The practice of mewing, therefore, offers significant benefits that extend far beyond facial aesthetics.

The Profound Health Implications of Nasal Breathing

The shift from mouth breathing to nasal breathing is a cornerstone of the mewing philosophy.

The health benefits are extensive and well-documented in medical literature.

Nasal breathing is crucial for the proper development of the paranasal sinuses.

These sinuses produce nitric oxide, a vital molecule.

Nitric oxide is a potent vasodilator, meaning it widens blood vessels.

This widening improves blood circulation and lowers blood pressure.

It also plays a key role in the immune system, acting as an antimicrobial agent.

When we mouth breathe, we bypass this essential nitric oxide production.

Mouth breathing also leads to a less efficient exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide.

The air inhaled through the nose travels deeper into the lungs.

This deeper travel allows for better oxygen saturation in the blood.

Chronic mouth breathing, especially during childhood, can have severe consequences.

It is associated with the development of a long, narrow face.

This is often referred to as adenoid facies or long face syndrome.

The constant open mouth posture allows the tongue to drop from the palate.

This lack of upward pressure leads to a downward and backward growth pattern.

The health consequences extend to sleep quality.

Mouth breathing is a major contributor to snoring and obstructive sleep apnea.

By forcing the tongue to the palate, mewing helps to stabilize the airway.

This stabilization is what reduces the likelihood of the airway collapsing during sleep.

The practice is a simple, non-invasive way to improve respiratory function.

It is a return to the fundamental mechanics of human respiration.

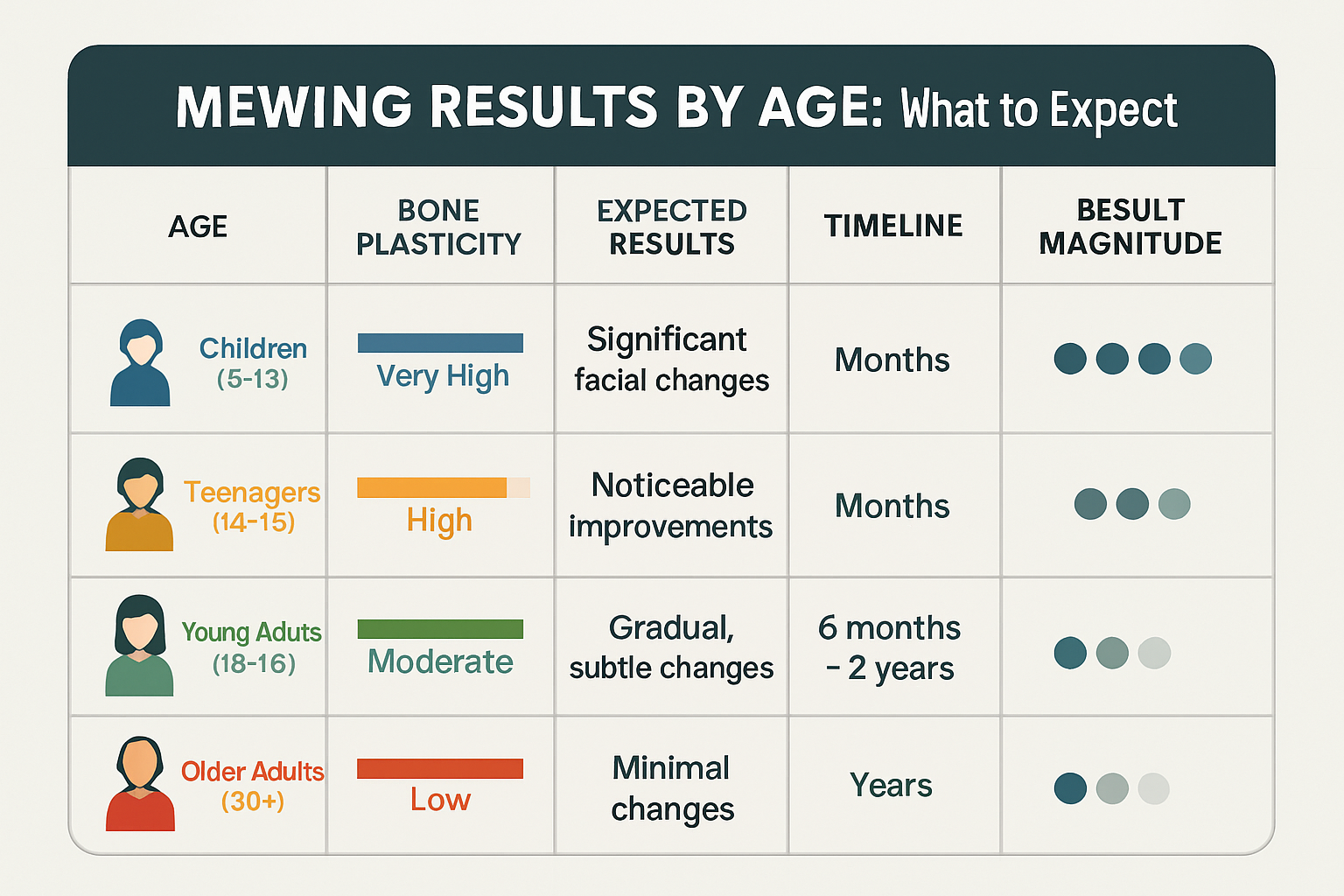

7: Age Comparison

The effectiveness of mewing is widely believed to be age-dependent.

The most significant and permanent changes are observed in children and adolescents.

Their facial bones are still growing and are highly malleable.

In this age group, consistent proper tongue posture can potentially guide the maxilla and mandible into a more favorable position.

This is the primary focus of the original Orthotropics philosophy.

For young adults (typically 18-25), noticeable changes are still possible, but they require more dedication.

Skeletal changes are slower, but muscular and soft tissue improvements can be seen within months.

The tightening of the submental area is a common and achievable result.

In older adults (over 25), the potential for skeletal change is minimal to non-existent.

The facial bones are fully fused, making significant bone remodeling highly unlikely.

However, mewing still offers the benefits of improved posture and muscle tone.

It can help combat the effects of aging, such as sagging under the chin.

The health benefits, particularly those related to breathing and sleep, are equally valuable at any age.

Patience and realistic expectations are crucial for individuals starting the practice later in life.

Age-Specific Expectations and the Window of Opportunity

Understanding the age-related limitations is vital for setting realistic expectations.

The window of opportunity for significant skeletal change is before the end of puberty.

During these formative years, the maxilla is still pliable.

The sutures, or joints, between the bones are not yet fully fused.

This is why Orthotropics focuses on early intervention.

The goal is to harness the body’s natural growth spurt.

For teenagers, the potential for change is still high, but the commitment must be absolute.

The pressure needs to be consistent to overcome the forces of established habits.

The use of appliances in conjunction with mewing can accelerate results.

For adults, the focus shifts entirely to muscular and soft tissue adaptation.

The bone structure is largely fixed, but the muscles are highly adaptable.

The toning of the submental muscles can take several months to become noticeable.

The most dramatic “before and after” photos in adults are often due to weight loss.

They are also often due to the correction of severe forward head posture.

It is important to be wary of claims of radical bone change in adults.

However, the health benefits remain a powerful motivator for all ages.

Improved breathing, better sleep, and reduced neck strain are universal gains.

Mewing in adulthood is a form of myofunctional therapy.

It is a way to maintain and optimize the function of the oral and facial muscles.

It is a commitment to preventative maintenance for the facial structure.

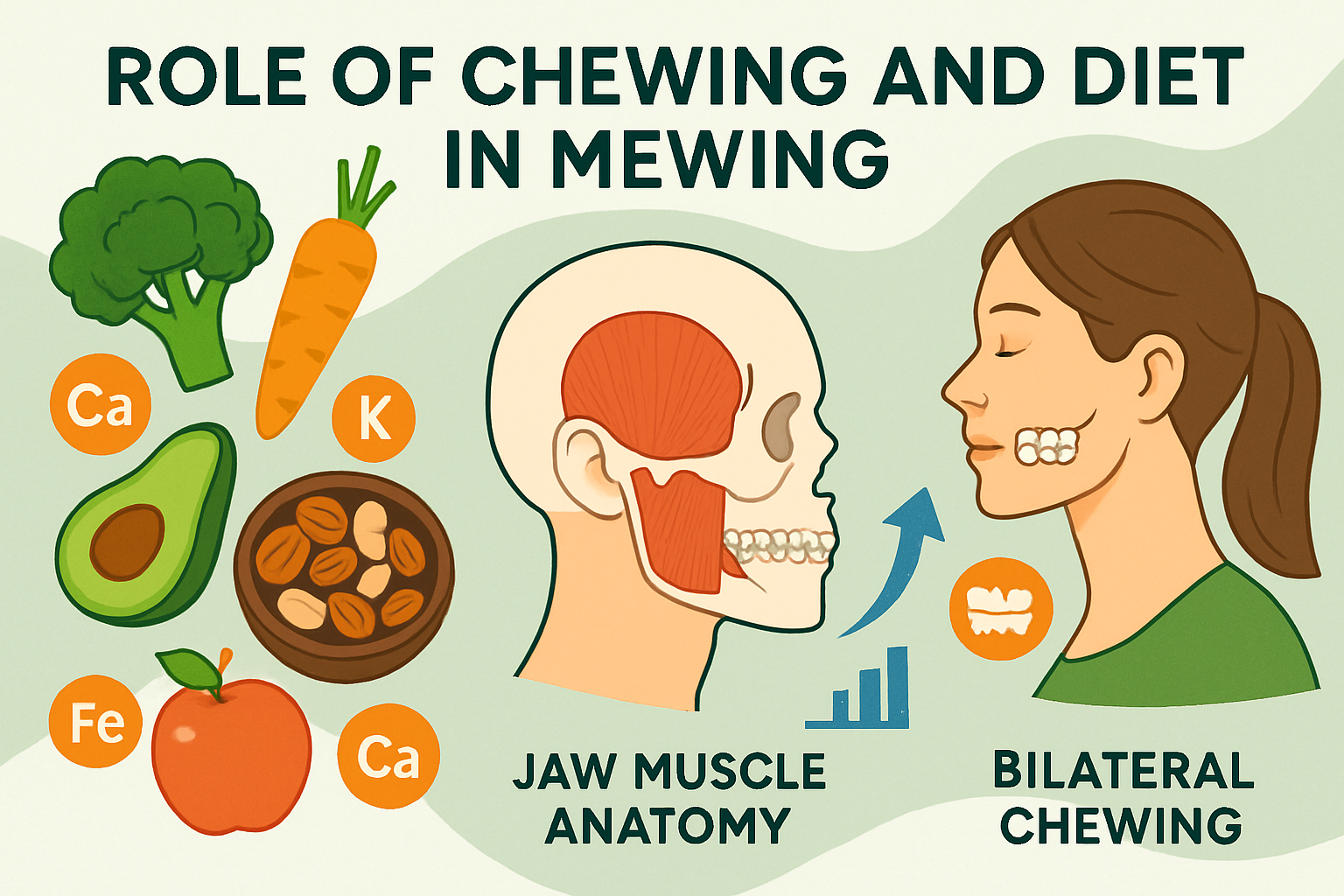

8: Diet & Chewing

Mewing is often presented as one component of a broader, more natural lifestyle.

A key partner to proper tongue posture is a harder, more natural diet.

Modern diets are often soft and processed, requiring minimal chewing effort.

This lack of masticatory stimulation is theorized to contribute to underdeveloped jaws.

Proponents of mewing advocate for incorporating hard, fibrous foods into the diet.

This includes raw vegetables, tough meats, and even specialized chewing gums.

Increased chewing strengthens the masseter muscles, leading to a more square jawline.

The act of chewing also stimulates blood flow and bone density in the jaw.

However, it is vital to approach hard chewing with caution to avoid TMJ issues.

Over-chewing or chewing on one side can lead to muscle imbalance and pain.

The focus should be on balanced, bilateral chewing to promote symmetry.

The combination of a harder diet and correct tongue posture creates a synergistic effect.

The chewing builds the muscle, while the mewing guides the underlying bone structure.

This holistic approach aims to reverse the effects of a lifetime of soft food consumption.

The Role of Mastication in Facial Development

The relationship between diet, chewing, and facial development is a central theme in Orthotropics.

Anthropological studies suggest that our ancestors had significantly wider jaws.

Their diets consisted of tough, raw, and fibrous foods.

This constant, intense chewing stimulated the growth of the maxilla and mandible.

The advent of processed, soft foods in the modern era has changed this dynamic.

Our jaws are now often underdeveloped due to a lack of masticatory load.

This underdevelopment is believed to be a major cause of crowded teeth.

The recommendation to chew hard foods is a direct attempt to reintroduce this load.

Chewing gum, especially hard, sugar-free varieties, is a popular tool.

It provides a convenient way to exercise the masseter muscles throughout the day.

However, the chewing must be balanced and symmetrical.

Chewing predominantly on one side can lead to facial asymmetry.

It can also cause hypertrophy of the masseter on the dominant side.

This imbalance can contribute to TMJ dysfunction and pain.

The key is to chew food and gum equally on both sides of the mouth.

The goal is to achieve bilateral muscle development.

The combination of mewing and hard chewing creates a powerful dual force.

The mewing provides the upward force, and the chewing provides the lateral force.

This holistic approach aims to maximize the potential for a strong, wide jaw.

It is a return to the evolutionary pressures that shaped the human face.

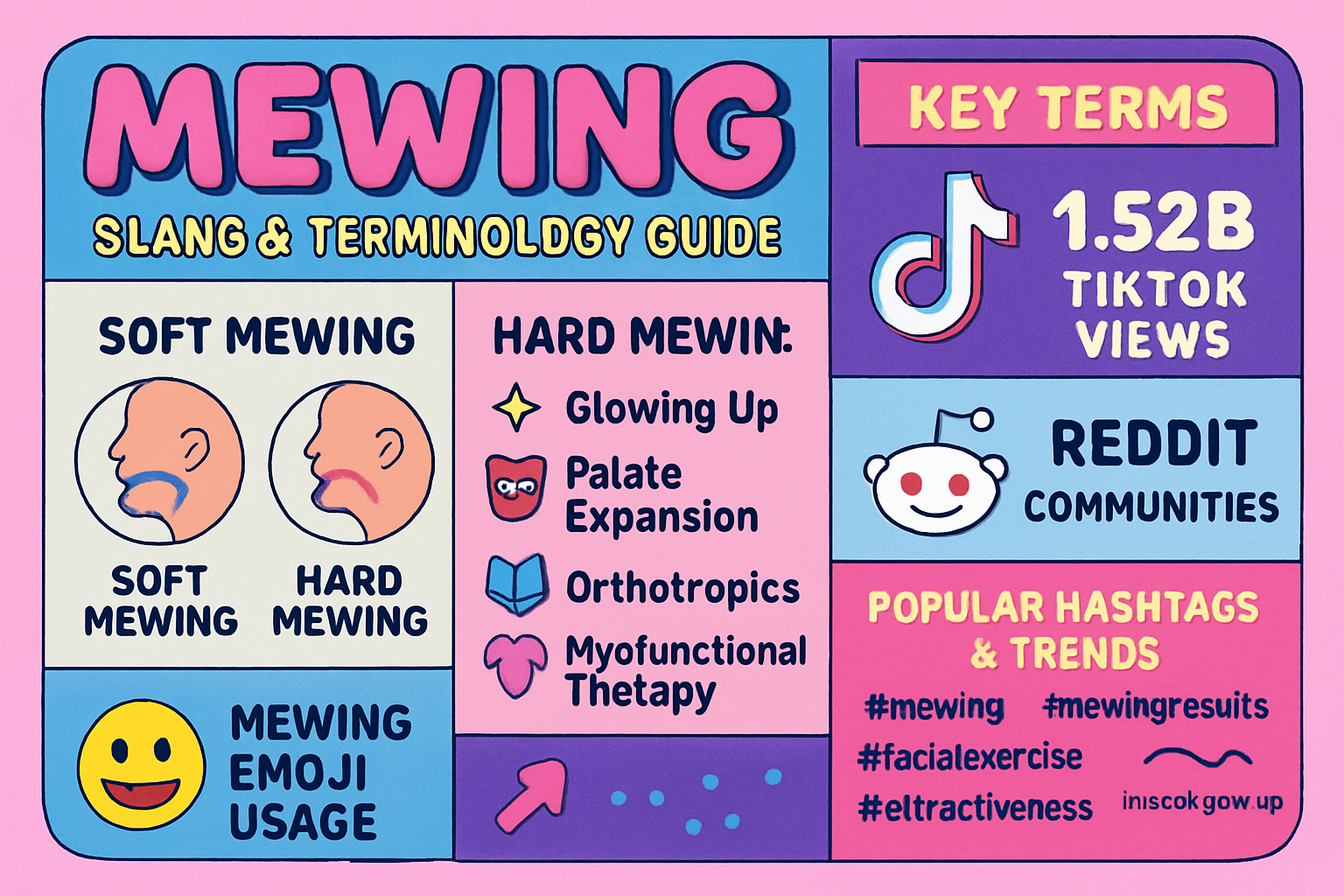

9: Viral Trend & Slang (Trendy infographic)

Mewing’s journey from an orthodontic concept to a viral sensation is a fascinating case study in internet culture.

The practice gained massive traction on platforms like YouTube, TikTok, and Reddit.

The term “mewing” itself became a popular slang term.

The most common slang usage is the “mewing face” or “mewing look”.

This refers to the subtle facial expression adopted when the tongue is correctly positioned.

It involves a sealed mouth, a defined jawline, and often a slightly intense gaze.

Another popular term is “maxxing”, which refers to maximizing one’s facial aesthetics.

Mewing is considered a key component of the broader “looksmaxxing” movement.

The trend is fueled by dramatic before-and-after photos and testimonials.

These visuals often exaggerate the potential results, leading to unrealistic expectations.

The viral nature has also led to the proliferation of misinformation.

Many online guides teach incorrect or even harmful techniques.

It is crucial for newcomers to seek information from reliable sources, despite the trend’s popularity.

The community surrounding mewing is passionate and highly engaged.

This collective enthusiasm has solidified its place in the modern aesthetic lexicon.

Decoding the Viral Slang and Community Culture

The viral spread of mewing has created its own unique subculture and vocabulary.

The term “looksmaxxing” is a key piece of this lexicon.

It refers to the pursuit of maximizing one’s physical attractiveness.

Mewing is often seen as the most fundamental, non-surgical component of this movement.

The community is highly active on platforms like Reddit’s r/Mewing and various Discord servers.

These forums are filled with progress pictures, technique discussions, and motivational content.

The slang term “hunter eyes” is often associated with the aesthetic goals of mewing.

This refers to eyes that appear more deep-set and hooded.

Proponents believe that forward growth of the maxilla contributes to this look.

The term “chewing gum” in the community often refers to specialized, hard mastic gum.

Brands like Falim or specialized jawline gums are frequently discussed.

The viral nature has a dual-edged effect.

It has brought awareness to the importance of oral posture to a global audience.

However, it has also led to the spread of dangerous misinformation.

Unverified claims of rapid skeletal change are common.

Some users advocate for extreme, painful techniques that can cause harm.

The community’s focus on aesthetics can sometimes overshadow the health benefits.

It is crucial to maintain a critical and informed perspective.

The core message of proper tongue posture and nasal breathing remains valuable.

The trend has successfully reframed the conversation around facial aesthetics and health.

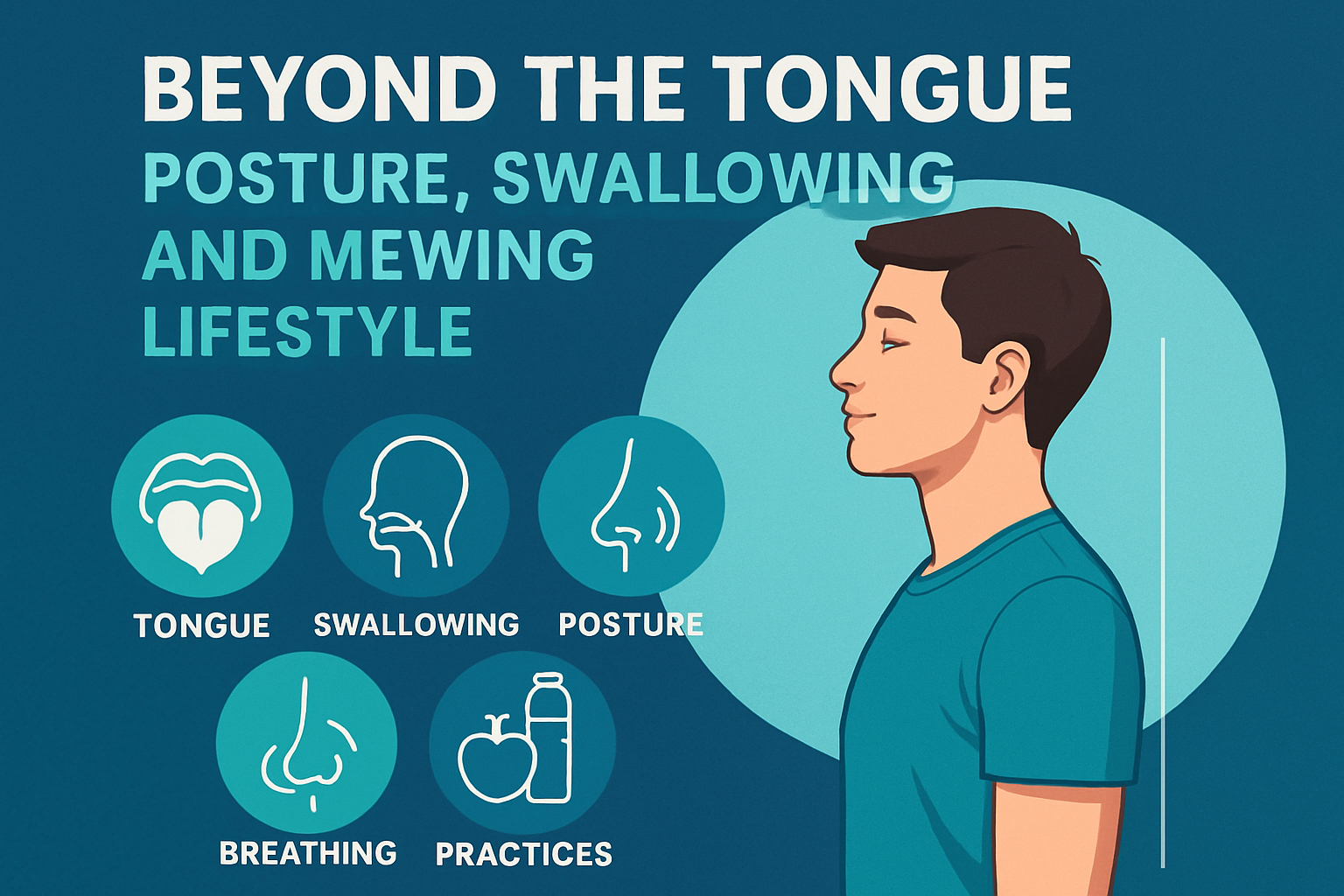

10: Lifestyle & Posture (5 Pillars)

Mewing is not an isolated exercise but a part of a comprehensive approach to health and aesthetics.

The practice is often integrated into a framework known as the Five Pillars of Facial Health.

The first pillar is Proper Tongue Posture, which is the core of mewing itself.

This involves the 24/7 commitment to keeping the entire tongue on the palate.

The second pillar is Nasal Breathing, which is a direct consequence of correct tongue posture.

It ensures optimal oxygen intake and prevents the negative effects of chronic mouth breathing.

The third pillar is Correct Body Posture.

Head and neck posture are inextricably linked to jaw position.

A forward head posture, common in modern life, pulls the jaw down and back.

Maintaining a straight back and neck allows the jaw to sit in its natural, forward position.

The fourth pillar is Proper Chewing and Diet.

This involves eating hard, natural foods and chewing bilaterally for muscle development.

The fifth pillar is Swallowing Technique.

A correct swallow involves the tongue pressing against the palate to push food down.

An incorrect swallow, or a tongue thrust, pushes the tongue against the front teeth.

Mastering all five pillars creates a holistic environment for optimal facial development and health.

These principles emphasize that true aesthetic change comes from a complete lifestyle overhaul, not a single trick.

The Five Pillars: A Holistic Approach to Facial Health

The Five Pillars framework provides a holistic roadmap for integrating mewing into a healthy lifestyle.

The first pillar, Proper Tongue Posture, is the constant, gentle upward force.

It is the foundation upon which all other pillars rest.

The second pillar, Nasal Breathing, is the immediate physiological benefit.

It ensures optimal oxygenation and nitric oxide production.

The third pillar, Correct Body Posture, is the alignment of the head and neck.

A simple test is to stand with your back against a wall.

Your heels, buttocks, shoulders, and the back of your head should all touch the wall.

This position naturally encourages the correct jaw and tongue placement.

The fourth pillar, Proper Chewing and Diet, addresses the need for masticatory load.

It is the active exercise component of the philosophy.

The fifth pillar, Swallowing Technique, is often overlooked but is critically important.

A correct swallow is known as a somatic swallow.

It involves the tongue pressing against the palate to move the food.

An incorrect swallow, or a visceral swallow, involves the use of cheek and lip muscles.

This incorrect technique can push the teeth out of alignment over time.

The constant, repetitive force of an incorrect swallow is highly detrimental.

Mastering the somatic swallow reinforces the correct tongue posture.

It turns the act of eating into a continuous, beneficial exercise.

These five pillars are interconnected and mutually reinforcing.

Neglecting one pillar can undermine the progress made in the others.

The ultimate goal is to make these five principles unconscious and automatic.

This is the state of optimal craniofacial function.

Conclusion: The Path Forward

Mewing represents a powerful shift in perspective, moving from passive acceptance of facial structure to active engagement.

While the scientific community remains skeptical of its skeletal claims in adults, the benefits to posture, breathing, and muscle tone are undeniable.

The practice demands unwavering consistency and a commitment to a healthier lifestyle.

By focusing on the five pillars—tongue posture, nasal breathing, body posture, diet, and swallowing—you embark on a journey of self-improvement.

Remember that results are gradual and often subtle, requiring patience over many months or even years.

Consulting with a professional, such as an Orthotropics practitioner or a myofunctional therapist, is always recommended.

The ultimate goal is not just a sharper jawline, but a return to the natural, optimal function of the human face and airway.

Embrace the habit, correct the mistakes, and let consistency be your guide.

This is the true essence of the mewing practice.

Final Thoughts on Commitment and Consultation

The commitment required for mewing is significant, but the potential rewards are substantial.

It is a journey of self-awareness and physiological correction.

The most common reason for failure is a lack of consistency.

Treat the practice as a fundamental part of your daily hygiene, like brushing your teeth.

For those with existing dental or jaw issues, professional consultation is paramount.

A myofunctional therapist can provide personalized guidance and exercises.

They can help correct deeply ingrained swallowing and posture habits.

An orthodontist can assess the underlying skeletal structure.

They can determine if there are any physical obstructions to nasal breathing.

Mewing should be seen as a complementary practice, not a replacement for medical care.

The focus should always be on health first, aesthetics second.

A healthy, functional oral system will naturally lead to a more attractive face.

The journey is long, but the destination is a more functional, aesthetically pleasing, and healthier you.

Embrace the challenge and commit to the optimal human resting posture.

This is the enduring legacy of the mewing movement.